Key Points

-

Intravital imaging captured microglia phagocytosing metastatic “seeds,” preventing colonization of the brain.

-

Two-photon microscopy and optical tagging enable us to analyze the microglia at the tumor–immune frontline.

-

Enhancing microglial activity in disseminated tumor stage may offer a new strategy to prevent brain metastasis.

Summary

A research group led by Research Fellow Takahiro TSUJI of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine (currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, United States) and Professor Hiroaki WAKE has visualized, for the first time, the very moment when the brain’s immune cells, microglia, directly engulf and eliminate disseminated tumor cells—the “seeds” of metastasis. Using advanced two-photon microscopy, which allows unparalleled live imaging of the brain, the team captured these critical interactions in real time.

Brain metastasis remains one of the most difficult cancer complications to treat, profoundly impacting patient survival. Until now, it has been unclear why microglia, normally the brain’s sentinels, sometimes fail to prevent incoming cancer cells from growing after they arrive via the bloodstream.

In this study, the researchers recorded the “battle” between microglia and cancer cells in live mouse brains using two-photon microscopy. They observed that while some microglia actively phagocytosed and cleared tumor cells, others paradoxically supported cancer cell survival and growth. To investigate these distinct roles, the team applied their newly developed “Opto-omics” approach, in which only the microglia physically interacting with tumor cells are selectively tagged with light, isolated, and analyzed. By integrating single-cell transcriptomics with longitudinal tumor profiling, they discovered that tumor-derived molecules such as CD24 act as “don’t eat me” signals, enabling cancer cells to evade microglial attack. Removing these signals restored robust microglial phagocytosis and dramatically suppressed brain metastasis.

These findings reveal a novel therapeutic strategy: harnessing the brain’s innate immune power to eliminate disseminated tumor cells before they establish metastases. The study paves the way for preventive medicine against brain metastasis.

This work was conducted in collaboration with Prof. Toyohiro HIRAI, Kyoto University, Teppei SHIMAMURA, Tokyo University of Science, and Hiroyoshi NISHIKAWA, the National Cancer Center Japan. The results were published online in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research on December 10, 2025 (December 11, 2025 JST).

Research Background

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related death. Among its forms, brain metastasis is particularly devastating, with limited treatment options and profound impact on both quality of life and survival. While therapies exist once sizable tumors have formed in the brain, almost no strategies directly target the very first disseminated cancer cell (“seed”) that arrives and lodges in the brain. One major reason is that these initial cells are extremely small—barely detectable even under a microscope—making their detection, isolation, and analysis extraordinarily difficult.

The brain, however, is equipped with immune sentinels known as microglia. These cells rapidly respond to pathogens and debris by engulfing and clearing them. But in the case of tumor “seeds” arriving through the bloodstream, do microglia act as defenders or as accomplices? This critical battle unfolds deep inside the brain during the first hours to days, and has long remained a black box.

Previous studies have relied largely on “snapshots” of fully developed metastases or surgically resected tissue. Such static observations could not reveal what happens in real time, or which cells directly confront cancer cells as they arrive. This limitation led to biased interpretations: the protective, phagocytic role of microglia was often underestimated, while microglia and related macrophages were more frequently classified as tumor-promoting. This prevailing view became a major obstacle in devising strategies to prevent metastasis at its earliest stage.

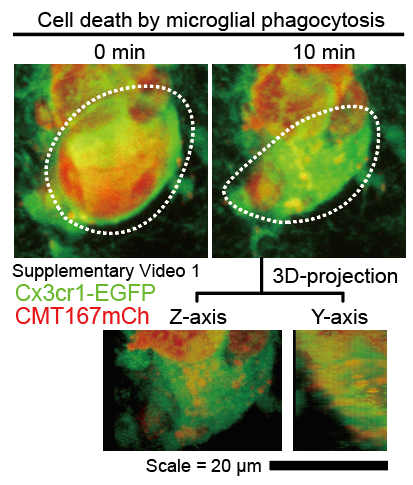

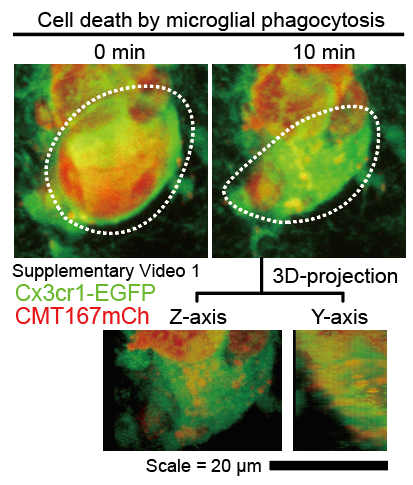

To overcome this barrier, the research team developed an approach to capture disseminated tumor cells in living mouse brains at single-cell resolution using two-photon microscopy. With this system, they recorded not only the moments when microglia actively eliminated tumor cells (Fig. 1), but also cases where microglia instead permitted tumor growth, enabling the formation of micrometastases. Based on these contrasting observations, the researchers hypothesized that microglia may acquire disease-specific functional states at the tumor interface.

To test this, they combined holographic two-photon microscopy with their newly established “opto-omics” platform. This allowed them to precisely tag with light, isolate, and analyze only the microglia that were physically engaging tumor cells at the frontline. By linking these dynamic, real-time interactions with downstream molecular analyses, they successfully connected tumor–microglia behavior to the underlying mechanisms at play.

This breakthrough opens the way to understanding how microglia decide between tumor clearance and tumor support, at the very first encounter. Importantly, it suggests a new therapeutic vision: amplifying the natural protective power of microglia at the earliest stage, to eliminate metastatic seeds before they take root. Such a strategy could bring us closer to a future where brain metastases are prevented before they ever begin.

Fig. 1 Microglia can phagocytose disseminated tumor cells

Research Findings

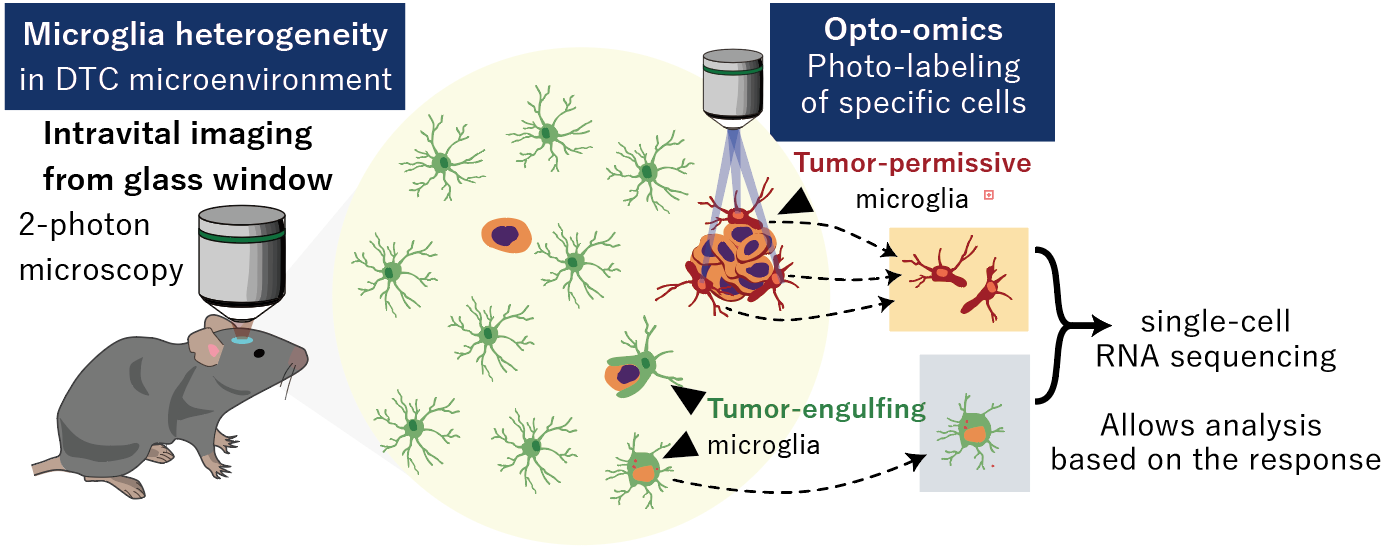

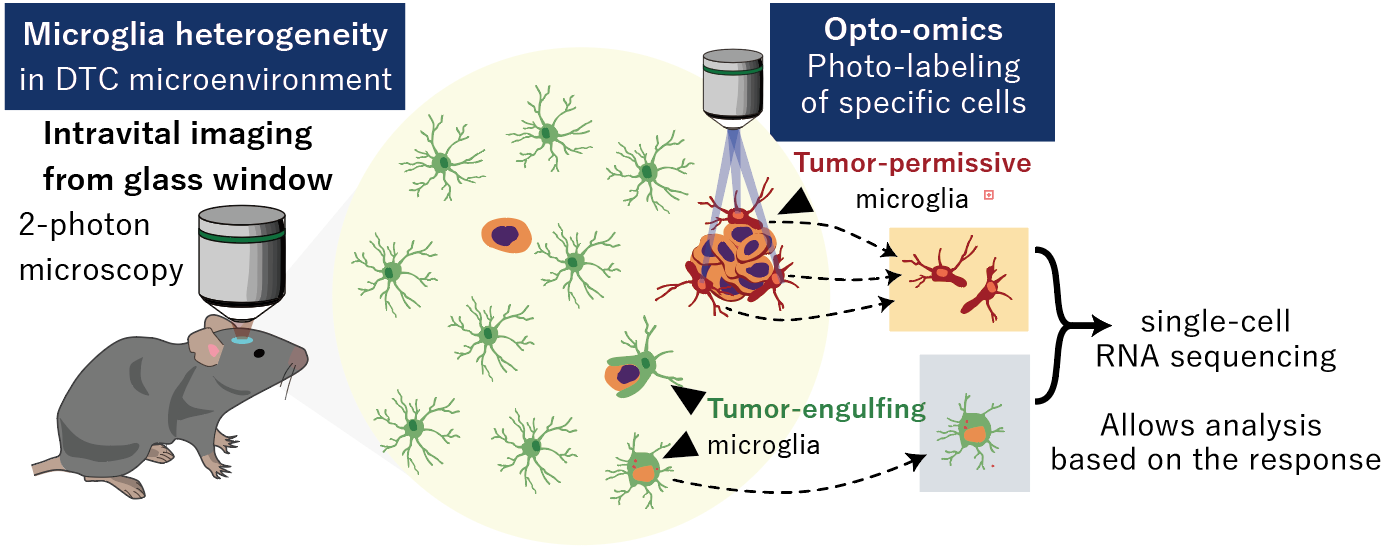

Fig. 2 Microglial heterogeneity and photo-labeling of specific microglia

1. Visualization of the “first moment” of brain metastasis

The research team developed a mouse model of early-stage brain metastasis from lung cancer. Using two-photon microscopy, they captured the decisive moment when microglia directly engulf and eliminate disseminated cancer “seeds.” This is the first high-resolution, in vivo recording of microglial phagocytosis of tumor cells, demonstrating that microglia can act as defenders against cancer through active engulfment (Fig. 1).

2. Discovery of microglial heterogeneity

Conventional understanding held that microglia primarily support tumor growth. By combining single-cell in vivo imaging with single-cell RNA sequencing, the team showed that not all microglia behave the same: some actively phagocytose cancer cells to protect the brain, while others promote tumor survival and growth. These findings provide direct evidence, from both microscopy and gene-expression patterns, that microglial responses in the brain are highly diverse (Fig. 2).

3. Optical tagging of tumor-adjacent microglia

The researchers further discovered that only microglia in close proximity to tumor cells undergo morphological and functional changes. To specifically analyze these frontline cells, they generated mice expressing the photoswitchable fluorescent protein PSmOrange2, which changes color from orange to near-infrared when exposed to a defined wavelength of light (930 nm). Using two-photon microscopy with holographic precision, they selectively illuminated only those microglia clustered around tumor cells, marking them for downstream analysis.

The photoconverted microglia were then isolated by flow cytometry and subjected to detailed transcriptomic profiling. Integrating these data with single-cell transcriptomics and computational analysis, the team identified molecular pathways involved in microglial phagocytosis of tumor cells. This approach linked direct, real-time evidence at the tumor site to underlying molecular mechanisms (Fig. 2).

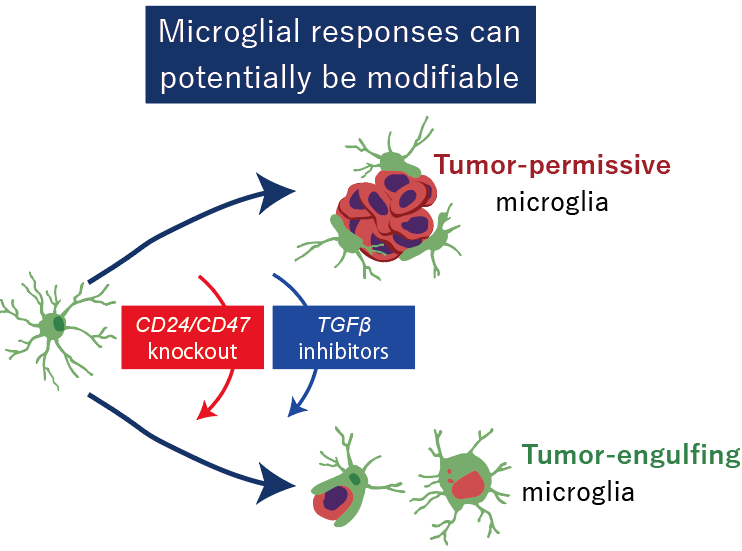

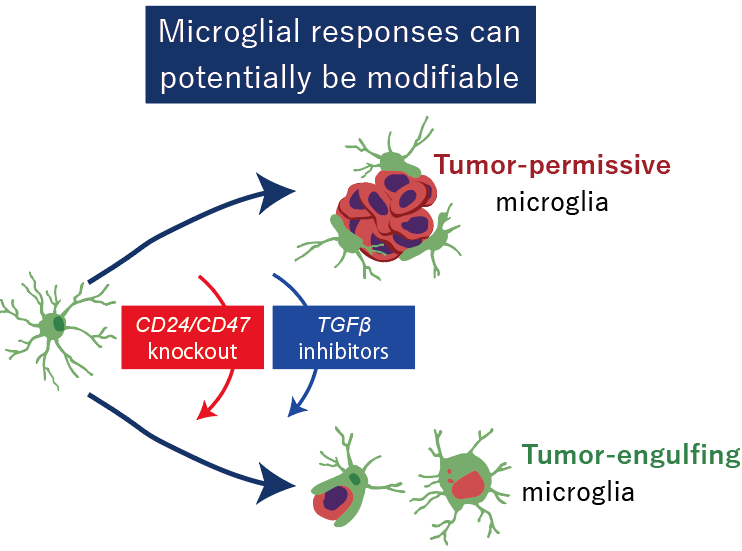

Fig. 3 Microglial responses can potentially be modifiable

4. Identification of the merit of “don’t-eat-me” signals

By analyzing tumor cells over time from dissemination to metastatic outgrowth, the researchers identified the cell-surface proteins CD24 and CD47 as key molecules enabling tumor cells to evade microglial attack. Blocking or removing these signals reactivated microglial phagocytosis and strongly suppressed brain metastasis (Fig. 3).

5. Clues toward clinical translation

Expression of CD24 and CD47 was also confirmed in human tumor samples, highlighting their potential as therapeutic targets and diagnostic biomarkers in brain metastasis.

Future Perspective

Looking ahead, the research team aims to develop preventive therapies that maximize the power of microglia at the earliest stage—before cancer cells can take root in the brain—to “nip metastasis in the bud.” At present, molecularly targeted drugs against CD47 exist, but there are no therapies that inhibit CD24. The team will work on optimizing inhibitors and antibody drugs against these targets, as well as designing strategies that combine them with immunotherapies and existing treatments.

In parallel, they will pursue the development of predictive biomarkers to identify which patients are most likely to benefit, paving the way toward personalized medicine. Furthermore, the researchers plan to expand this framework—real-time imaging coupled with opto-omics—to other cancer types and organs, aiming to establish a versatile platform for controlling the earliest stages of metastasis. This approach may also provide new insights into the roles of microglia in other neurological diseases.

Acknowledgement

This study is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) (20H05899 to H.W.); Fostering Joint International Research (B) (20KK0170 to H.W.); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (18H02598 and 21H02662 to H.W.); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (JP25H01217 to H.W.); the Uehara Memorial Foundation to H.W.; Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST (Grant Numbers JPMJCR1755 and JPMJCR22P6 to H.W.); Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), CREST (JP23gm1410011 to H.W.); programs for Bridging the gap between R&D and the Ideal society (Society 5.0) and Generating Economic and Social Value (BRIDGE) to H.W.; Moonshot R&D Programs (Grant Numbers JP24zf0127012, JP24zf0127010, and JPMJMS2012 to H.W.); Adopting Sustainable Partnerships for Innovative Research Ecosystem (Grant Number JP23jf0126004 to H.W.); and the Research Foundation for Opto-Science and Technology to H.W. Additionally, it was supported by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE) (Grant Number 21cm0106587h0001 to T.T.); a Research Fellowship for Young Scientists by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Grant Number 21J01531 to T.T.); JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 21K16140 to T.T.); an ACT-X grant from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (Grant Number JPMJAX2229 to T.T.); a research grant from the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science to T.T.; and a research grant for medical science from the Takeda Science Foundation to T.T.

Publication

Journal: Cancer Research

Title: Microglia Display Heterogeneous Initial Responses to Disseminated Tumor Cells

Authors: Takahiro Tsuji1,2, Haruka Hirose3, Daisuke Sugiyama4, Mariko Shindo1, Rahadian Yudo Hartantyo1, Yutaro Saito1, Tsuyako Tatematsu1, Shota Sugio1, Makoto Sambo5, Masumi Hirabayashi5, Yasuhiro Kojima3, Jun Koseki3, Kazutaka Hosoya2, Hiroshi Yoshida2, Tatsuya Ogimoto2, Yuto Yasuda2, Kentaro Hashimoto2, Hitomi Ajimizu2, Yuichi Sakamori2,6, Hironori Yoshida2, Noritaka Sano7, Masahiro Tanji7, Hiroaki Ito8, Kazuhiro Terada8, Masatsugu Hamaji9, Toshi Menju9, Hiroyuki Konishi10, Shogo Kumagai11,12, Cyrus Ghajar13, Daisuke Kato1, Hiroshi Date9, Akihiko Yoshizawa8,14, Yoshiki Arakawa7, Hiroaki Ozasa2, Andrew J Moorhouse5,15, Teppei Shimamura3, Hiroyoshi Nishikawa4,11, Toyohiro Hirai2, Hiroaki Wake1,16,17.

1Department of Anatomy and Molecular Cell Biology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, 466-8550, Japan.

2Department of Respiratory Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, 606-8507, Japan.

3Division of Systems Biology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, 466-8550, Japan.

4Department of Immunology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, 466-8550, Japan.

5National Institute for Physiological Sciences, National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS), Okazaki 444-8585, Japan.

6Department of Respiratory Medicine, Japanese Red Cross Society Wakayama Medical Center, Wakayama, 640-8558, Japan.

7Department of Neurosurgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, 606-8507, Japan.

8Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, 606-8507, Japan.

9Department of Thoracic Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, 606-8507, Japan.

10Department of Functional Anatomy and Neuroscience, Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya University, Nagoya, 466-8550, Japan.

11Division of Cancer Immunology, Research Institute/Exploratory Oncology Research & Clinical Trial Center (EPOC), National Cancer Center, Tokyo 104-0045/Chiba 277-8577, Japan.

12Division of Cellular Signaling, National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan.

13Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle WA 98109, United States.

14Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara, 634-8521, Japan.

15Department of Physiology, School of Medical Sciences, UNSW Sydney 2052, Australia.

16Division of Multicellular Circuit Dynamics, National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan.

17Department of Physiological Sciences, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI, Hayama, 240-0193, Japan.

DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-25-3425

Release Source

Nagoya University

Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST)

Institute of SCIENCE TOKYO

National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS)

5251